Aside from LU decomposition we discussed previously, QR decomposition is another prominent method to decompose a matrix into a product of two matrices. In QR decomposition, a matrix is factorized into an orthogonal matrix

and an upper triangular matrix

such that

. QR decomposition can be applied to any square and rectangular matrix with linearly independent columns.

There are several ways of computing and

, namely the Gram–Schmidt process, Householder reflections, and Givens rotations. However, in this article, we focus on applying Householder reflections to compute such matrices, thanks to its simplicity and excellent numerical stability (the Gram–Schmidt process is known to be inherently unstable whereas the Givens rotations are significantly more complex to implement). For simplicity, let us assume that

is square such that

. To find

and

, we iteratively compute symmetric and orthogonal matrices

for

such that:

where . The idea here is to transform each column of the original matrix such that the resulting column is zero below the main diagonal. To better illustrate how this works, suppose that we start with an unstructured matrix:

where the symbol represents any real number. Now we start with finding

such that

is structured in the form of:

Notice that the first column of the matrix has zeros below the main diagonal. Next, we compute

such that:

This process is repeated times in total until we get

that is an upper triangular matrix.

Now that we understand the big picture of the algorithm, the next important question is, how can we leverage the Householder reflection to find ? To be able to illustrate the mechanism of Householder reflection, let us restrict ourselves to the case where

, i.e., two-dimensional case. The lecture by Toby Driscoll is an excellent source to understand the application of Householder reflection in QR decomposition. The main idea here is to treat the matrix

as a reflection operator to a particular mirror axis. In our case when

, we want to find

such that, when it is multiplied to the vector

which represents the first column of

, it gives:

where is the

-th standard basis vector. It is important to note that the above equation exists since

must be orthogonal. From the above, we can clearly see that the operator

somehow “moves” the vector

into the axis in the first dimension. Define a new vector

to represent the difference between the two, i.e.:

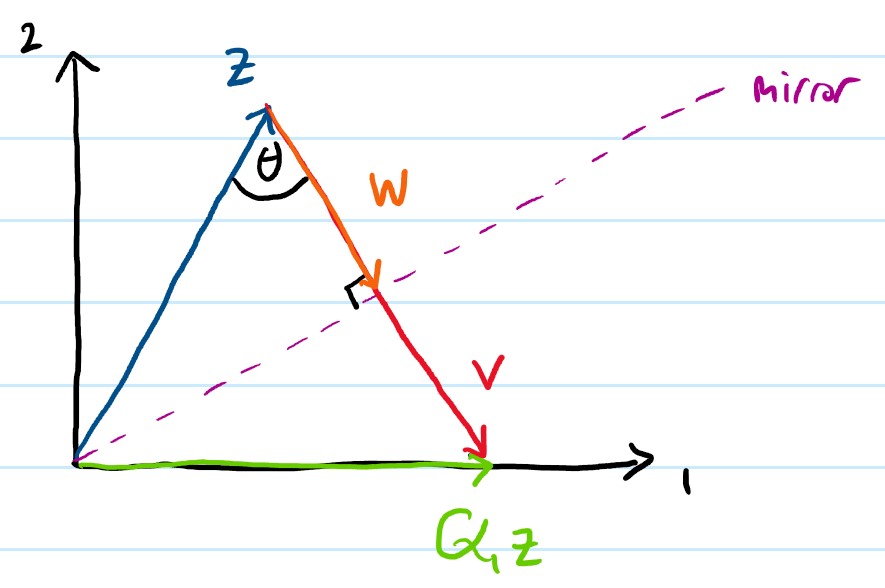

The above vectors as well as the mirror are illustrated in the figure below:

From the figure above, (blue) and

(green) are mirrors to each other with respect to the mirror axis (purple). We define an auxiliary vector

(orange) which is simply a half of

(red). Now, we want to find out what

really is in terms of magnitude and angle. The magnitude (or the length) of

is equal to:

Instead of finding the angle (or direction) of , we can simply use the unit vector of

. As such,

is simply:

This results in:

which implies that:

where . One can easily confirm by the definition of orthogonality that

is in fact orthogonal.

The above process is repeated to obtain and so on until

. However, since we do not want to change the previously computed columns, one only needs to apply the Householder reflection to the remaining rows (from the main diagonal to the end). I would recommend you to also check out the Wikipedia page about QR decomposition for some numerical examples.